Doing the right thing

On the day Nelson Mandela died, 5 December 2013, there was nothing to be taken aback about in Chancellor Dirks' homage to a man whose long, honorable, and storied life spanned the roles of lawyer, non-violent activist, armed revolutionary, political prisoner, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, South Africa's first post-apartheid president, and modern archetype of principled resolution.

From Chancellor Dirks' statement, titled We are united in grief and reverence for Mandela:

Today, we are all part of a global community united in grief and reverence for a man whose clarity of moral purpose and extraordinary perseverance brought freedom to the oppressed, hope to the hopeless and light to all the dark places where human dignity struggled to survive. Today, we pause to not only mourn, but also to reflect, with gratitude, on the good fortune we had to witness in our times all that Nelson Mandela accomplished and exemplified.True enough, and I was glad that the leader of my alma mater (and current employer) saw fit to honor Mandela on behalf of himself and of UC Berkeley as a whole.

Doing the wrong thing

But consider that during the mid-1980s anti-apartheid movement, the University of California administration stood in direct opposition to the students, staff, faculty, and community members demanding that UC divest its portfolio of multiple billions of dollars in investments tied to apartheid South Africa.

In fact, the university administration and governance board were the target of the anti-apartheid movement's divestment demands.

Hence my surprise when I read further into Chancellor Dirks' statement:

At Berkeley we also remember the special ties that will forever bind our campus to this man and his movement. As we know, the Bay Area was the epicenter of the American anti-apartheid activity due, in no small measure, to the passionate engagement of Berkeley students. In 1990, on a worldwide tour after serving 27 years in prison, Mandela spoke to a crowd of 60,000 at the Oakland Coliseum. During that speech South Africa's future president specifically cited our university’s "Campaign Against Apartheid" as having been particularly significant in hastening the end of white-minority rule in his country. That recognition highlights what is, in my opinion, one of Berkeley's proudest moments.One of the university's proudest moments? That Berkeley's solidarity movement registered on Nelson Mandela's map of international struggle for justice in South Africa?

Yes, Chancellor Dirks got that right too.

But I felt a jarring dissonance to see the Chancellor of 2013 taking pride in, and institutional credit for, a movement that he now embraces -- but that his predecessor at Berkeley's helm, Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman, tried ruthlessly to destroy ... and that UC's then-President David Pierpont Gardner opposed on principle. Here, from a post-apartheid interview with Gardner, circa 1998:

I opposed divestment for reasons that I thought were sufficient. [...] After having studied the issue very carefully I concluded that the university, I'm not talking about individuals, the university acting collectively as a corporate entity ought not to divest. We didn't invest in South Africa because of apartheid; I thought we shouldn't divest because of it. And there were a lot of other arguments for remaining as against leaving.The anti-apartheid movement of the mid-1980s -- including all the thousands of Berkeley students, staff, faculty, alums, and community members who participated in it -- was on the right side of history. The UC Berkeley and University of California administrations, and the UC Board of Regents, had to be shamed, badgered, and ultimately cornered into doing the right thing.

They didn't yield easily. The university's leaders used threats, intimidation, and police force in their attempts to derail our movement. From the Christian Science Monitor of 10 April 1986:

After last Thursday's melee, in which 91 protesters were arrested and 28 civilians or officers injured, Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman said, "The violence was about as bad as anything that happened in the '60s." [...]Our protests were provocative and illegal? Our protests in solidarity with those struggling for their lives against apartheid? Oh my!

Although antiapartheid protesters have been highly visible on campus for the past two years, this year's protests "have been provocative and illegal from the beginning," says university spokesman Ray Colvig. The university has responded, he says, with tough measures that have not been used since the Vietnam war protests -- the use of force by police, banning about 40 nonstudent activists from campus, and raising the possibility of suspension or academic probation for protesting students.

Telling the truth

While Chancellor Dirks wasn't at Berkeley during the 1980s anti-apartheid movement, he was a professor on another university campus at that time (the California Institute of Technology, a.k.a. Cal Tech). He cannot have been unaware of anti-apartheid activism that swept hundreds of universities in that era. So I think it's reasonable to expect that the Chancellor -- an historian -- had sufficient context to reflect on the role played by leaders at the institution he now heads, rather than to blithely appropriate credit and pride for a movement his office opposed.

Institutions change. As an alum and a longtime member of the campus staff, I welcome the moral evolution of the University of California at Berkeley

But better to acknowledge history than to smother it in nostalgia.

It's particularly necessary to acknowledge history when the risk of repeating historical mistakes remains high. How high? Have a look at this recent video of UC Police beating a crowd of students and faculty (and, if you like, my analysis of what happened, and how the UC Berkeley administration so badly mishandled the campus Occupy Cal protest on 9 November 2011 that then-Chancellor Birgeneau had to walk his initial statement pretty much all the way back: When authorities equate disobedience with violence).

What's a good model for institutional evolution in relation to activism, in which the institution does frankly acknowledge history?

It's worth looking at UC Berkeley's relationship to the Free Speech Movement of 1964:

The Free Speech Movement pitted Berkeley students against a university administration intent on keeping a national struggle for civil rights off campus. In a very small nutshell, the administration lost that fight, and the university became a better institution for it.

Now, and since February 2000, the campus undergraduate library's entrance is flanked by the Free Speech Movement Café, privately funded decades after the fact ... but with the administration's permission and support. At the café, tables display flyers and newspaper articles under their clear acrylic surfaces that convey a history of the FSM through primary materials: students and other visitors can see and interpret for themselves. The space is used explicitly to generate critical discussion about contemporary social and political issues ... that is, for the very same, prohibited 'extra-curricular' activity that the FSM had to fight for in 1964. Yeah, you might detect a whiff of nostalgia beneath the heady perfume of espresso, but sentimentality is tempered by focus on actual issues, tensions, conflicts, resolutions ... and history.

In 1997, thirty-three years after FSM, the steps leading to Sproul Hall were named in honor of Mario Savio, arguably the FSM's most charismatic and articulate leader. The Sproul steps have served as a stage for countless demonstrations over the years. If you've never seen him in action, take a minute and a half to watch Savio inaugurate this iconic alter of campus activism a half-century ago this year:

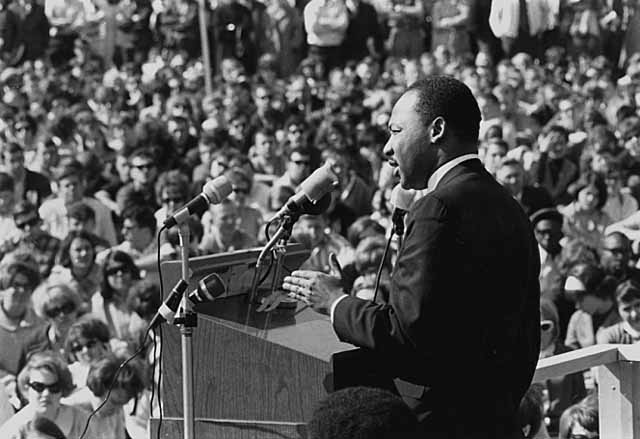

The still-photo included at the top of this post shows Mario Savio addressing an anti-apartheid protest on Sproul Plaza during the spring of 1985, twenty years after the speech excerpted in the video. You can spot him if you look carefully for the balding fellow just a wee bit up and left of the center of the image, in a tan sport coat. Or if you'd rather, follow the red arrow in the cropped and marked image below. (Thanks to Laura A. Watt for permission to use her photograph.)

History doesn't end.

Setting the record straight

Since December, following a proposal made by UC Berkeley staff member and anti-apartheid movement participant Anne Stinson, there's been talk of renaming Lower Sproul Plaza for Nelson Mandela. The site is down another set of steps from the back of the crowd pictured in this post. (That plaza is currently under redevelopment.)

I think that renaming Lower Sproul would be more than fitting.

It would be a way to set a struggle for justice mounted in the 1980s into the very infrastructure of the campus, a struggle that pitted students, staff, faculty, and community against the poor judgment of Berkeley's administration (since corrected). Doing so might help to counter the facile, grating, but nonetheless persistent mainstream media narrative that student movements for social, political, and economic justice began and ended "in the sixties," a falsehood at Berkeley and elsewhere.

It would recognize that there are times when the view from the top of a great university is distorted, and that the way forward needs to be charted by its students, to whose generation our common future belongs. (I'm aware of at least one signatory to this morning's letter from the Campaign Against Apartheid whose son recently graduated from UC Berkeley. It would surprise me if there weren't others, sons and daughters alike, who are already or will someday be graduates themselves.)

You can support renaming Lower Sproul Plaza for Nelson Mandela on Facebook's CalMandelaPlaza page.

You're entitled to an opinion, because you're almost certainly affiliated with the Berkeley campus. Even if you're not a student, alum, or employee, you help fund the institution if you pay taxes in California and/or the United States: UC Berkeley is a state university, and received a third of a billion dollars in federal research funding in 2013 alone. Make your voice heard.

For the record, I'll end with the text of the Campaign Against Apartheid piece as submitted to the Daily Californian and published (with minor edits) today. I'm including the full set of signatories -- 61 as of this morning; the newspaper only published those of the six of us who drafted the op-ed and organized the collection of signatures. [UPDATE: late-arriving signatures added after the publication timestamp of this post.]

Last month, upon the death of Nelson Mandela, UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks released a statement asking us to “remember the special ties that will forever bind our campus to this man and his movement.” The chancellor called “the Bay Area the epicenter of the American anti-apartheid activity due, in no small measure, to the passionate engagement of Berkeley students.” The chancellor wrote that when Mandela spoke at the Oakland Coliseum after his release from prison in 1990, “South Africa’s future president specifically cited our university’s ‘Campaign Against Apartheid’ as having been particularly significant in hastening the end of white-minority rule in his country. That recognition highlights what is, in my opinion, one of Berkeley’s proudest moments.”

As members of the Campaign Against Apartheid, and participants in Berkeley’s diverse, multi-group, multi-racial anti-apartheid movement, we thank Chancellor Dirks for his recognition of what we accomplished almost thirty years ago.

While the current chancellor now celebrates that accomplishment and that commitment, it is important to recall that back then both the system-wide and Berkeley campus administrations were hostile to the movement. Why their hostility? Because since the 1970s, anti-apartheid activists at UC Berkeley (and at all the other UC campuses and at hundreds of colleges and universities nationwide) made our demand not of the Apartheid government but of our own institution. We called on the UC Regents to fully and immediately divest -- to sell off -- all UC investments in companies and banks that operated in or loaned to South Africa. That local focus as part of an international effort against racial oppression gave the movement great appeal and power.

The UC administration, however, (like campus administrations across the country) depicted foreign companies as a progressive force for change in South Africa, despite what Mandela, the ANC and every other anti-apartheid organization in the country had been saying for decades. Even black labor unions in South Africa -- with their own jobs to lose -- had called for corporate withdrawal from their country as part of a broad strategy to isolate and weaken the Apartheid regime. But the UC president and a majority of the Regents kept increasing their investments in those companies. By the 1980s, UC had by far the most South Africa-linked investments of any university – more than $3 billion.

University authorities did not oppose the divestment movement with words and ideas alone. The Berkeley administration endeavored to physically intimidate the movement, especially the group we were part of, the Campaign Against Apartheid. For 18 months, when persuasion and enticement didn’t work, the administration used campus police (and eventually a dozen other police forces) to confront and suppress demonstrations -- strong-arming, punching, kicking, clubbing and otherwise assaulting, injuring, arresting and jailing students, employees and community members as they gathered, chanting ‘Free Nelson Mandela’, on Biko (Sproul) Plaza and at Crossroads (California Hall) Shantytown. Police seized divestment leaflets, wrestled away our literature tables, confiscated sound equipment and ripped down anti-apartheid banners, symbols and signs. The administration bullied students with bannings, monetary fines, conduct code hearings, and threats of suspension and expulsion.

Galvanized by the administration’s repression of campus protest and by the greatest uprising in South African history, Berkeley students and employees and community members from around the Bay Area created in the mid-1980s what remains the largest and most sustained militant movement on a campus since the Sixties. We were also successful.

Not mentioning either the movement’s focus on changing university investment policy or the reaction of UC officials and the Berkeley campus administration obscures what happened at that time. So, while pleased that Chancellor Dirks has proposed an educational event about Mandela’s accomplishments, we would like to suggest a program that also examines Berkeley's divestment movement. More permanently, the suggested re-naming of Lower Sproul as Nelson Mandela Plaza could be augmented with a permanent installation or exhibit documenting the contribution of Berkeley students, staff, and community in supporting the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

Signed (updated as of 12 Apr 2014): Bradley Angel, Robert Arnold, Alice Bell, Patty Berne, David Blackman, Bill Bogert, David Böhner, Andy Brodie, Joanna Burroughs Manqueros, Dave Campbell, Andy Clardy, Marcel Côté, Alan Crowley, Brendan Cummings, Michael Delacour, Michael Donnelly, Henry (Hummer) Duke, Mickey Ellinger, Larry Engel, Isis Feral, Leslie Firestone, Stuart Fisk, John Fox, Steve Gilbert, David Grumio, Monica Gyulai, Graham Hale, Ross Hammond, Rita Himes, Odile Hugonot Haber, John Hurley, Nancy Hurley, Jae Kimball, Jennifer Knight, Jeff Kravitz, Vicki Legion, Joe Liesner, Steve Masover, Mark McDonald, Al Miller, Jeff Miller, William Nessen, Osha Neumann, Holly Ober, Michael Pachovas, Andrea Pritchett, Heidi Rand, Patricia Seery, Alan 'Felix' Shafer, Victor Silverman, Amandeep Singh, Jim Squatter, Michael Stack, Heidi Starr, Michael Strange, Susan Stryker, Dean Tuckerman, Max Ventura, Rodney Ward, Jeremy Warren, Roy Werbel, Jonathan Winters, Stan Woods, Ken Yale, Eddie Yuen

Related posts on One Finger Typing:

What Nelson Mandela actually said in Oakland on 30 June 1990

Remembering Richie Havens: down to earth

Nelson Mandela and the death of UC Berkeley's Eshleman Hall

When authorities equate disobedience with violence

Again, thanks to Laura A. Watt for permission to use her photograph of Mario Savio speaking at an anti-apartheid protest on Sproul Plaza in 1985.